Echoes from Wuhan: The Past as Prologue

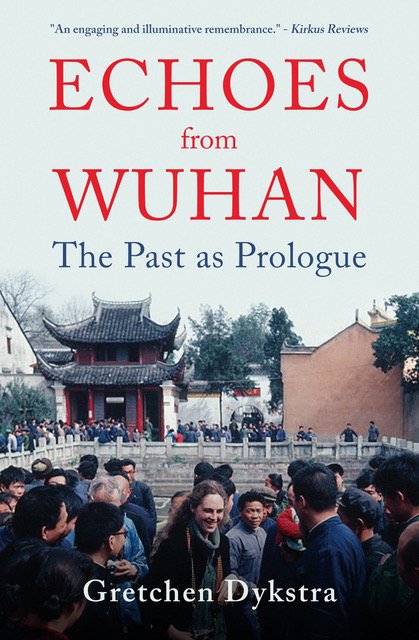

Echoes from Wuhan tells the dramatic, fast-paced story of a naïve and adventuresome young American woman and how she navigated—well and not so well—the complexities of cross-cultural confusions and clashes in China long ago.

A prisoner of privilege and watched by Party officials, Gretchen Dykstra stayed two years and returned to a career in civic affairs of New York City. She maintained enduring friendships with some of her students and, through those bonds, reveals aspects of an ancient culture that shape modern China.

Published by Atmosphere Press

available now

What People Are Saying About Echoes From Wuhan

“As a teacher in China, Dykstra weaves in historical summaries for context, but the heart of her narrative rests in the complicated, personal stories of the students and teachers with whom Dykstra became close… She makes effective use of classroom discussions and free-time conversations to illustrate a vast cultural and philosophical divide...”

Kirkus Reviews

“With Echoes from Wuhan, Gretchen Dykstra has given us a precious account of what it was like to live in China from 1979 to 1981, at the very beginning of Deng Xiaoping’s Reform and Opening policy. This book is a reminder of all the ways in which China has changed, as well as all the ways in which it has remained the same. I found it especially fascinating—and, in some cases, shocking—to learn what it was like for Dykstra to reconnect with Chinese friends decades after they met in Wuhan.”

Peter Hessler

staff writer for the New YorkeR

and author of four books about China

"While libraries strong in Chinese culture and history will find her memoir appealing, armchair and destination travelers to China and those who look for a blend of entertainment and enlightenment will also find Echoes from Wuhan a compelling read. The China of yesteryear comes to life under her hand…”

Midwest Book Review

“You do not need to be a Sinophile to enjoy Echoes from Wuhan… She makes friends, sometimes enemies and describes them with candor. She is a young Jean Brodie and her syllabus…is as unorthodox. .. She often breaks the rules with insouciance; not so easy as she is under almost permanent surveillance. She is indomitable and this is what makes her story so compelling.”

Blog BelleW

“Dykstra provides a unique window into what it means to be a responsible, caring, open person—as a teacher and a friend.”

INDEPENDENT BOOK REVIEW

“Most fascinating of all, we encounter over and over, as does the author, the deep and powerful historical heritage of Chinese culture and the way it shapes and defines everything from parent-child relationships to marriage and romantic relationships. “

PETER GOLDMARK, PUBLISHER

INTERNATIONAL HERALD TRIBUNE (1998-2003)

“This is a terrific book. I’m the author’s sister and might therefore be accused of bias, but that does an injustice…Her fearlessness, endless curiosity, and deeply American sense of fair play and independence constantly crashed up against a culture with very different (and often unknowable) rules. She’s a good writer and the book leaves a deep impression. It’s both an easy read and packs a punch.”

Alison Dykstra, Gretchen’s sister

“Truth being stranger than fiction, this memoir which reads like a well written novel, includes jealousy-inspired murder, match-making, ill-advised romance and political intrigue. And also episodes of warm encounters and cross-cultural friendships, as Dykstra succeeded in winning the trust and affection of her students…This book gave me a new perspective on current events related to Wuhan and China/US relations. I highly recommend it.”

Anonymous Amazon Reviewer

Author's Note

Most Americans had never heard of Wuhan before coronavirus emerged there in 2019, but then the industrial capital city of Hubei Province entered our collective consciousness and re-emerged in mine. I lived there from 1979 to 1981 when the Chinese government hired me and 99 other Americans to teach English in colleges around the country.

Whether it is Covid ravaging the world, President Xi and his open disparagement of democracies, or the fierce competition between our two nations, many Americans now think of China, its style, and its ambitions as the boogeyman of the world. I hear it all the time.

Sometimes the comments come in a polite discussion about geopolitics, sometimes in chats about selective public high schools and the high ratio of Asian students in them. Sometimes the comments are thinly veiled racist comments, and, too often, I hear—as we all do—about violence against Asians, usually defenseless older women. Anti-Chinese sentiment is clearly on the rise. Many non-Chinese Americans seem to have a hard time understanding or even liking a behemoth nation with such a different worldview and an unnerving capacity to succeed.

The comments invariably take me back to my days in China and I think about the complexities of cross-cultural interactions and the differences I experienced. Just as my presence helped my students better understand American qualities of independence, self-reliance, and informality, my Chinese friends taught me things about China.

When I hear debates about the prevalence of Chinese kids winning seats at selective high schools or elite colleges, I think about my friend who helps Chinese-Canadian kids polish their writing skills in her Vancouver garage on weekends. When I hear people marvel at the diligence of the quiet Chinese couple in my little Hudson River town, I think of my friend in Toronto and her resilience. I disparage the hunger of the Communist Party and think about my friend who plays the game masterfully. And I watch diplomats foolishly shame Chinese leaders and think of my friend’s paralyzing disgrace.

Dedication to education, for sure, respect for hierarchy and order, yes. Determination, nationalism, and pride, yes. Straightforward, sometimes. Impenetrable, sometimes. Gracious, invariably.

My strong relationships with four in particular—and my complicated relationship with the local Communist Party officials—now shape my reactions to the current drumbeat of the China talk I hear.

When I arrived, the nation was shattered: Chairman Mao had died; the Cultural Revolution was just over, but its deeply negative impacts were still felt. With a massive and extremely poor population, China was determined to regain its strength and reclaim its prestige after decades of foreign aggression, national weakness, and internal brutality. For the United States, the sheer size of the market—however poor—was too seductive to ignore. After almost 30 years of hostile accusations and total separation, our countries began to inch towards one another—each believing it had the superior system.

The Chinese propaganda machine was ubiquitous, centralized, and relentless, painting Americans as untrustworthy and heartless. And me? I was the epitome of the innocent abroad, unable to speak Chinese, never having studied its history or its literature in school, but enamored of its isolation. It was seductive to a restless soul like me and the singularity of the adventure appealed to me.

English was foundational to China’s future success and so at Wuhan Teachers’ College, where I was assigned, I taught English to two distinct groups of students: The young teachers at the college who had been “worker-peasant-soldier students” during the Cultural Revolution and then ordered to stay at the college to eventually teach English. The second group was part of the first cohort to enter college after the Cultural Revolution; unlike the young teachers, they had passed highly competitive, national entrance exams. Both groups were diligent; some students were brilliant, and a few fiercely ambitious.

I lived as a prisoner of privilege on the small campus, closed to other foreigners, and threw myself into a tiny corner of a complicated nation. I have not been back to China since 1982, but I watched from afar as China plotted its renewal and enacted its own rebirth. I watched the protests—and later the massacre of young people—in Tiananmen Square in 1989 and I went to Hong Kong to witness the hand-over. I watched as China’s government embraced getting rich, not public service, and built new cities higher and higher and farther and farther out in the countryside. I watched as thousands upon thousands of American businesspeople and tourists flocked to China, and American colleges actively recruited Chinese students, who can now pay full tuition. I watched as China financed and built roads, bridges, and railroads throughout the developing world.

Then the supremely confident President Xi Jinping tightened the reins on his nation, shifting it, if not back to a totalitarian state, squarely into an authoritarian one. I watched as his crackdown on corruption in the Community Party, the military, the business world, and American multinational corporations won him plaudits. He flexed his military might with India and Taiwan and has claimed the South China Sea and the land below it. He has demanded changes to Hong Kong’s democratic political system and has sent thousands of Muslim Uyghurs to “re-education” camps, exacting a high price for many because of the violent acts of a few. He has dramatically beefed up Chinese soft power in media, universities, and think tanks, often using, I am told, overseas Chinese to endorse the perspectives of the Chinese Communist Party. He has limited access to Western news and entertainment for the Chinese. He reminds me of some of my experiences, albeit in a richer, technologically advanced, and now confident nation.

***

The book is divided into three parts: The first part describes a dreary but energetic China before it prospered, and the life I lived for two years, trying hard—and at times failing—to navigate the expectations students had for me and rules the Party laid for me.

The second part covers the summer of 1982 when I convinced a Party leader in New York to grant me permission to return alone to Wuhan for a week. I went and was reminded of all that is good about Chinese people and the power of the Party.

In Part Three, I trace what I learned from my experiences in China that partially shaped my future professional life and what has happened to some of my students and, specifically, a devoted mentor, an artistic soul, a corporate titan, and an ashamed murderer. Their lives were similar then, but they are different in their temperaments and varied in their choices.

I have changed everyone’s names, but if any of my old students happen to read this book I am sure they will know who they are. I am indebted to them for giving me such a rich two years and apologize to them for my naivety. I am particularly appreciative of those friendships that have survived through all these decades.